Cultural Autonomy

Currently the National Government is way out of touch with regular human beings; and no matter which party is in power, the train seems to be trying to jump the tracks. Many Americans long want to return to simpler times when the decisions that affect our lives were made at the local level. Except during times of all out armed conflict and war, the power of this democratic society should be locally reserved and respected. This concept is Constitutionally enshrined in the Tenth Amendment. It states that any power that is not given to the federal government is given to the people or the states.

Traditionally those who have recognized the validity of the above statement have argued for increased State’s Rights. As appealing as the State’s Rights argument is, there exists a better alternative. Below, you will find a brief discussion of why State’s Rights advocates miss the mark, followed by a description of a better alternative.

Immediately, after the American Revolution the idea of State’s Rights was a much more viable option. Thomas Jefferson and many of the Founding Fathers were ardent supporters of State’s Right, and they were deeply distrustful of the trappings of monarchy. They had, after all, just fought a war to put an end to European Monarchy here in America. A seismic shift away from top/down control and towards local autonomy would have been much easier then, because there were only thirteen colonies, each of which had distinct economic interests and concerns.

However, things have gotten considerably more complicated since our early days. States in the United States have been gradually forming since 1787. Many living citizens were born before Alaska and Hawaii became states in 1959. A variety of treaties, purchases, wars, and Acts of Congress have extended the United States to the fifty states we now recognize. The arbitrary way that states borders have been drawn is the biggest flaw in the State’s Rights argument. Since most state boundaries were drawn by politicians for political reasons that no longer exist, much of the political and legislative underpinnings have disintegrated.

There is no significant reason why Nevada, for instance, should be politically distinct from Arizona. Those two states will always be friendly rivals on college gridirons, but their political needs are almost completely linked.

The states stopped being states except in name only in 1865. After the civil war the states abrogated their powers to the Federal government, and since then, they have been mere provinces. The Constitution put the nails in the coffins of States. Lincoln nailed them shut and buried them deep.

History imposes arbitrary and divisive distinctions on us. These distinctions, though effectively meaningless, tend to perpetuate themselves. Often state lines slash through and divide areas whose people share regional values and beliefs.

With many potential flaws, the State’s Rights movement remains an appealing alternative. However, even better would be to invest the political power of the states into larger, culturally unified areas, so that existing cultural values can be recognized, empowered, and accepted.

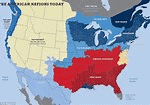

Colin Woodard, in his book American Nations, discusses the cultural groups that created the continent of North America by immigration, sometimes expanding from initially small settlements but often from massive waves of newcomers. See a 2013 Washington Post article and map by choosing this link: https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2013/11/08/which-of-the-11-american-nations-do-you-live-in/?utm_term=.9f202f51a817

Mr. Woodard points out that the old metaphor of the American “Melting Pot” never fully materialized; or, if it did, the fondue in the American crock pot has melted a little but was never stirred. The cultural values of the earliest successful migrants still exist unchanged despite later waves of population movement. As evidence of this phenomenon, Mr. Woodard cites cultural geographer Wilbur Zelinsky who formulated the Doctrine of First Effective Settlement in 1973.

After reading Mr. Woodard’s book, you will retrospectively see plenty of evidence of your own. Everyone knows, for instance, that people in coastal California are very different from people from the Deep South or New York City.

The outdated political realities of colonialism have saddled us with many subtle problems and have left many Americans feeling disenfranchised and cut off from their cultural identities.

Why continue to pretend otherwise?

Proposed: Let’s eliminate the fifty state legislatures and reallocate those legislative powers in a more meaningful way by transferring those powers to Mr. Woodard’s culturally unified American Nations. In the order he presents them in his introduction, they are: Yankeedom, New Netherlands, The Midlands, Tidewater, Greater Appalachia, the Deep South, New France, El Norte, the Left Coast, the Far West, and First Nation.

The following descriptions have been adapted from both Mr. Woodard’s book and the 2013 Washington Post article mentioned above:

Yankeedom: Founded by Puritans, residents in Northeastern states and the industrial Midwest tend to be more comfortable with government regulation. They value education and the common good more than other regions.

New Netherland: The Netherlands was the most sophisticated society in the Western world when New York was founded, Woodard writes, so it’s no wonder that the region has been a hub of global commerce. It’s also the region most accepting of historically persecuted populations.

The Midlands: Stretching from Quaker territory west through Iowa and into more populated areas of the Midwest, the Midlands are “pluralistic and organized around the middle class.” Government intrusion is unwelcome, and ethnic and ideological purity isn’t a priority.

Tidewater: Founded by land grants to the younger sons of southern England gentry, these coastal regions in the colonies of Virginia, North Carolina, Maryland and Delaware tend to respect authority and value tradition. Once the most powerful American nation, it began to decline during westward expansion.

Greater Appalachia: Extending from West Virginia through the Great Smoky Mountains and into Northwest Texas, the descendants of Irish, English and Scottish settlers value individual liberty. Residents are “intensely suspicious of lowland aristocrats and Yankee social engineers.”

Deep South: Dixie still traces its roots to the caste system established by masters who tried to duplicate West Indies-style slave society, Woodard writes. The Old South values states’ rights and local control and fights the expansion of federal powers.

El Norte: Southwest Texas and the border region, extending roughly one hundred miles north and south of the U.S./ Mexico border, is the oldest, and most linguistically different, nation in the Americas. Hard work and self-sufficiency are prized values.

The Left Coast: A hybrid, Woodard says, of Appalachian independence and Yankee utopianism loosely defined by the Pacific Ocean on one side and coastal mountain ranges like the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada’s on the other. The Left Coast was founded by merchants, missionaries, and woodsmen arriving on ships and farmers, prospectors, and fur trappers arriving by wagon. The independence and innovation required of early explorers continues to manifest in places like Silicon Valley and the tech companies around Seattle.

The Far West: The Great Plains and the Mountain West were built by big industry, as a source for raw materials and open land. The Far West has historically been somewhat isolated and remote because of the harsh, sometimes inhospitable climates and the vast stretches of the Great Plains. Far Westerners are intensely libertarian and deeply distrustful of big institutions, whether they are railroads and monopolies or the federal government.

New France: Former French colonies in and around New Orleans and Quebec tend toward consensus and egalitarian, “among the most liberal on the continent, with unusually tolerant attitudes toward gays and people of all races and a ready acceptance of government involvement in the economy,” Woodard writes.

First Nation: The few First Nation peoples left — Native Americans who never gave up their land to white settlers — are mainly in the harshly Arctic north of Canada and Alaska. They have sovereignty over their lands, but their population is only around 300,000.

Mr. Woodard has also identified culturally distinct differences between northern and southern Mexico and northern and southern Canada.

Historically, there have always been clashes between these cultural “nations,” but there need not be. Once cultural nations are recognized and celebrated, most of the reasons for dissension should disappear.

States Without Borders

State of Florida, state of mind and state of health are some of the states we can make statements about. According to https://www.usgovernmentspending.com/Florida_state_spending_2018, the State of Florida in fiscal year 2018 spends 76.5 billion dollars. The largest category is Health Care, $32.7 billion. The next largest is Education at 11.7 billion. Each registered voter is allowed one vote in an election while the amount of state taxes paid by each voter varies greatly. There are ways to equalize votes and payments.

Suppose a Florida citizen would prefer California’s health care program and New York’s education program. The programs could become separate states without borders and anyone could enroll in them. California Health could have regular elections and referenda, the enrollee would pay a voluntary amount and the number of his votes depends on the number of shares that he purchased. The relationship between purchased shares and benefits could be decided democratically. Benefits would be in the form of vouchers that could be used anywhere.

Similar voluntary arrangements could be made with education, pensions and parks. Roads, police and antipollution functions would still be funded by State taxpayers because enforcement is territory dependent and directly affects all residents.

True Democracy! How soon can we begin?

Next election, then the next one and…

Accurate history is always enlightening. I have not yet read American Nations but based on the descriptions I have provisionally prejudged it to be true as an historical account. I think that the differences between the regions are lessening while differences within an area persist. For example, in a typical large city compare the highest poverty neighborhoods with the highest wealth neighborhoods. Those areas also differ markedly in other qualities such as ethnicities, cognitive abilities, crime rates, entertainment choices, political beliefs, speech patterns, marriage rates, schooling, and more.

The existing State boundaries can be an annoyance to US citizens and people do relocate to better jobs, warmer climate and lower taxes. Of the set of political problems in the US, State borders is a miniscule issue and not worth changing. I think the big issues for US governance are:

1. Missile defense is inadequate to deter nuclear annihilation from Russia and China.

2. Automatic, “nondiscretionary” spending on subsidies are growing faster than the economy. They are immoral, unsustainable and destructive. Abolish all subsidies in all forms. Abolish government debt.

3. Government at all levels is too large and distorts private market choices. Get government out of the business of wage determination, schooling and entertainment (stadium subsidies, parks, etc.). Permanently shrink government.

4. Abolish income, payroll taxes, business and death taxes. Replace them with retail sales taxes.

States should be allowed to merge, divide or secede. No big deal, really.

Yes, differences “between the regions are lessening…” but they still persist. Wilbur Zelinsky, Pennsylvania State University, 1973, the Doctrine of First Successfully Settlement.